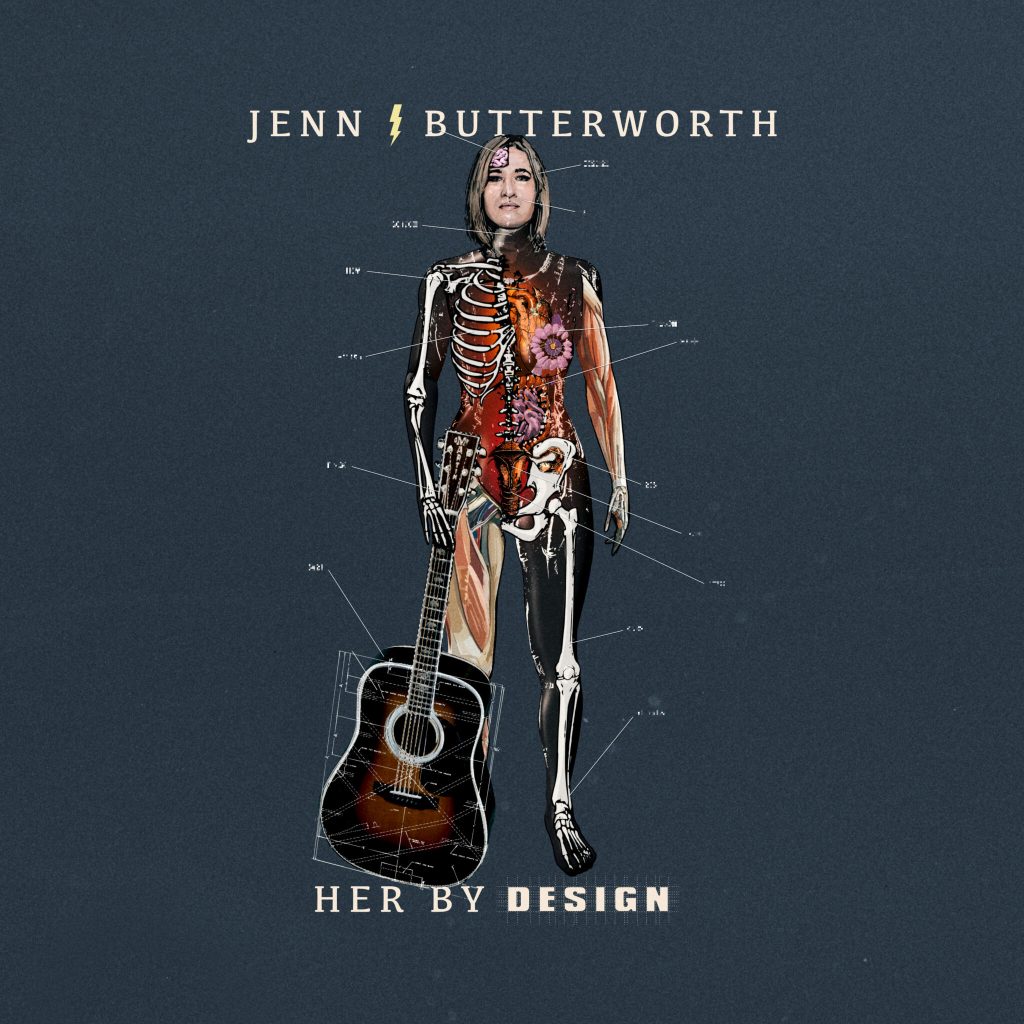

It is not often that a listener comes across something that feels entirely new, but Her By Design from Jenn Butterworth accomplishes the task — not by throwing out convention, but by diving deep into tradition.

The self-produced and self-released record is a captivating meld between the contemporary singer-songwriter form and Butterworth’s own deep ties to the much older Scottish folk music tradition.

Together, these two foundational pillars allow Her By Design to stand as a work that is both familiar to the modern ear and drastically different. These artistic conditions provide a basis, steeped in meaning, fit to present the album’s central subject matter: the complex and multifaceted experiences of womanhood.

An example of masterful storytelling, the album’s light and airy textures offer a musical reflection of the windswept Scottish landscape. The recording is as clear and crisp as the fresh, ocean-kissed air of a nation surrounded by the Atlantic and has a raw elemental power that reflects the enduring and untamed Highlands.

“All Our Days,” the album’s opening piece, makes this clear. It is a triumphant composition that simultaneously evokes a Fleetwood Mac hit and a theatrical score comprised of traditional instrumentation. The song introduces us to Butterworth’s vision — a worldview as interested in the movement of the Earth’s tectonic plates as it is in the life of a single insect. The world Butterworth offers in the song is one of sweeping, universal awareness — a profound and joyous celebration of a full life, well-lived.

The piece establishes a clear and keen sense of the subjects and aesthetics that encompass Her By Design.

Released in February, Butterworth’s solo debut is far from the beginning of her career. The folk guitarist and singer, based in Glasgow, Scotland, is a recognized name in the region’s folk music, having been part of a series of successful groups within the tradition.

Among her many contributions is her participation in Songs of Separation, a musical endeavor that addressed the 2014 referendum on Scottish independence. Organized by double-bass player Jenny Hill, the group of ten women folk musicians from Scotland and England, including Butterworth, spent a week recording an album addressing the subject on the Isle of Eigg. Recorded in June 2015, the collaborative work was selected as the winner of the “Best Album” category in the 2017 BBC Radio 2 Folk Awards.

On its second track, Her By Design moves from its unvanquished opening to “Little Sparrow,” another traditional, a gentle, sorrowful tale of the hardships of unfaithful romantic love and the conclusive rejection of it.

Whereas “All Our Days” offers a modern interpretation of a Scottish reel — a driving song intended to be accompanied by dance — “Little Sparrow” provides our first taste of Butterworth’s own explication of a modern ballad: sweeping, intimate, and dignified.

Like the album’s opening thesis, “Little Sparrow” carries with it a deep, melancholic appreciation for the moment despite the dejection conveyed. The beauty of the ballad’s gentle instrumentation encourages and reminds the listener that there is sanctity in the difficult moment, as there is in all of the many chapters that make up a lived life.

Then comes “Fair Maids of February,” a reinterpretation of a song originally recorded in 1980 by English folk musician Robin Dransfield.

At the core of the piece is the flower the song shares its name with. Snowdrops, as the flowers are also called, bloom from January to March in the region and are a common sight in churchyards and woodlands.

The flower was also the subject of a short poem by Victorian poet Lord Tennyson.

Butterworth’s interpretation offers the work as a contemplative ballad centered on plucked strings and ringing bells that reflect the final days of winter and the droplets of melting spring snow. Her new recording of the classic introduces a driving bridge that brings even more emotion to the piece and reiterates that the flowers described in the song symbolize the end of the long, hard darkness of winter, giving way to the promise and purity of the coming light of longer and warmer days.

“My folks used to play Robin Dransfield’s album a lot when I was a kid, and I remember this song from when I was a tiny person growing up in Mytholmroyd,” Butterworth explained in a post accompanying an acoustic performance of the song. “I’m lucky enough to be ‘looking after’ my folks’ record collection now, which is brilliant.”

The album continues with “The Housewife’s Lament,” another piece of vivid storytelling. Like the prior song, this is a reinterpretation of an established piece. The song originates from the diary of Mrs. Sara Price, who lived in Ottawa, Illinois, during the Civil War. Price lost all of her children, who died during the time of war. Her words, including the opening line “Life is a toil and love is a trouble,” led to the composition of a poem titled “A Housekeeper’s Tragedy” by Eliza Sproat Turner. Turner first published the work without attribution to either herself or Price in Arthur’s Home Magazine in 1871. Over time, the work became a folk song and was reintroduced when folk singer Peggy Seeger recorded it as “The Housewife’s Lament” for the 1968 album Female Frolic by the Critics Group, released on Argo Records.

An excerpt from the 1950s and 1960s folk music magazine Sing Out! reads: “She [Price] had seven children and lost them all. Some of her sons were killed in the Civil War. Thus, this version can be dated about mid-nineteenth century. It sounds like a composed song, written in the United States, not Ireland; although the tradition is that of Irish topical ballads. It has been variously titled ‘Life Is a Toil’ and ‘Housekeeper’s Lament.’”

Across its various interpretations, the work speaks to the unrecognized and unpaid hardships of domestic labor from women, but Butterworth approaches the song with her crystal-clear sound and unique traditional rhythms, bringing new life to a piece that spans generations.

The album then returns to an original composition from Butterworth with “A Toast.” Another tale of unfaithful love, this piece offers an enthralling narrative of revenge, heightened by compelling string interludes that sweep through the recording — a unique, driving rhythm embellished by a dynamic and carefully layered vocal performance.

“One in Ten” then slows the pace of the album, offering another ballad — this time depicting a woman struggling with illness. It is a tragic, meditative, and enthralling story led by guitar and a dynamic percussion section.

“I wrote this song recently about endometriosis, a condition where tissue similar to the lining of the uterus grows in other places in the body, causing a great deal of pain,” Butterworth shared. “Although one in ten women are affected by endometriosis, there hasn’t been a lot of research into causes and treatments.”

The piece holds the most intimate moments on the album, with Butterworth’s voice presented almost in a whisper to the listener. It also brings the sound of the album toward modernity with the inclusion of a synthesizer swell that both opens and closes the song.

This intimacy and central theme of womanhood continues with “Jeanie,” another reinterpretation of a traditional — this time, the Scottish folk ballad “Annachie Gordon,” also known as “Lord Saltoun and Auchanachie.”

The song tells the story of Jeanie, a young woman who, against her will, is forced by her father to wed the old and wealthy Lord Saltoun while her true love, Auchanachie Gordon, is away at sea. She agrees to the marriage, but the forced union leads to Jeanie’s death from a broken heart on her wedding night. Her true love returns to find her dead, kisses her cold lips, and also dies of a broken heart.

The tragic ballad clearly exhibits Butterworth’s ability to convey emotion through her vocal performance. It is her voice that carries this song — the longest on the record — for its entirety.

The most orthodox composition of the record is followed by what is perhaps its most modern interpretation.

Closing the album, “Her Smile Haunts Me Still” tells the story of a weary traveler yearning for a love from the past. Accented by delay effects, sweeping strings, and a modern groove, Butterworth’s interpretation brings the traditional into the modern era.

Originating from the 1860s, the song was written by Englishmen J.E. Carpenter and W.T. Wrighton. The piece was popular in both the United States and the Confederate States of America and became part of the nation’s compendium of folk songs.

With driving percussion, Butterworth transforms the piece from its theater-centric, operatic beginnings into a fully formed modern rock ballad, incorporating sections that reflect the call-and-response tradition found in blues music and its ancestors.

Her By Design paves the way for something wonderful and new. It does so not by throwing out the past, but by working with it hand in hand. Butterworth has made a piece of art that stands as a document showing how time, changing worldviews, and technology can bring about significant changes to existing texts — and how those texts can serve as a foundation for new creation.

In doing so, the compositions that comprise this recording stand as a beacon to the reality that Brittonic and Goidelic folk music is not only deeply feminine but have significantly influenced the songwriting traditions of the United States. The album provides a partial roadmap of how modern Americana music has come to be. It gives the listener a means to reverse-engineer the tradition and see how these traditional songs led to Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land,” Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind,” and, perhaps most appropriately, works like “Until It’s Time For You To Go” from Buffy Sainte-Marie.

Most importantly, as a piece of music and a work in its own right, Her By Design compels the listener to return again and again.