Chaz Knapp is forging ahead with his own unique practice, blending traditional instruments with a process tied to conceptual music and performance art to establish an idiosyncratic expression of Americana.

Working deep within the Ozark Mountains, this Arkansas-based artist blends his knowledge and mastery of traditional instruments with a willingness to experiment using a field recording process and on-site improvisations from the rugged landscape of tree-covered mountains, deep caverns, remote springs and winding rivers.

Winter Music is Knapp’s latest collection of improvisations from the mountain range. This time, the artist is sharing a repertoire of work made during the deep winter months. It is in direct conversation with his previous work of on-site improvisations made during the region’s hot summer.

Through this grounding but unconventional work, the artist considers place and time through a meditative creative process, creating a contemplative look at landscape through music and a portrait of winter in America’s heartland.

In preparation for Winter Music’s Dec. 5 release on Austin’s Aural Canyon record label, Knapp spoke with Sound Dissection to discuss the project and his process.

This conversation has been lightly edited for clarity.

❖ ❖ ❖

Sound Dissection: What initially compelled you to get out of the studio and make recordings outdoors?

Chaz Knapp: It was a change in landscape and a transition in life. I had been in a musical rut for a few years, and I got out of that by beginning to improvise on a combo organ. Those organ records got me having fun with creating music again. Soon after the organ sessions, my partner and I moved from Dallas to Arkansas. I became very connected to the landscape, and my love of the Ozarks became integrated with the freedom that improvisation brought me.

Can you share the process of making these recordings? Could you start by explaining how you selected the sites for these works?

The process came up by accident. As with most musicians, capturing field recordings is a special pastime. It was raining one spring day, so I decided to sit on my porch and record the storm. I then grabbed a tape recorder to record it. The tape player had a tape loop instead of a full 90 minutes, so I recorded a tape loop, and when played against the storm, it created a lovely texture. I grabbed a few more tape players, recorded some quick loops with my little three-string instrument and improvised. When I listened back a few weeks later, I was pleasantly surprised by how raw yet beautiful it was. It was so very ambient, but in this organic way that I felt really connected to. I decided to explore this further. Microfolk was done in the heat of summer, and afterward I had the idea to see how that change in seasons would contrast the first Microfolk sessions.

What do these places look like? Where are they? Are they very remote?

The places varied. All the places are in Northwest Arkansas. The Boston Mountains are nestled within the Ozarks. The terrain is beautiful and rugged: various streams, large sandstone rocks, limestone bluffs and countless waterfalls within oak and pine forests. Most of the recordings took place near creeks, within large sandstone rock formations, nestled in the woods, in an abandoned building or just at a local park. At most, we would have to hike in a mile, as I was worried about reality and convenience when doing these sessions.

Do these places have a personal significance to you?

Not particularly. I mainly wanted to explore making music this way because it affects my overall creative outcome. I am confined to only that moment, so choosing a location just got me in that creative mind-set; therefore, I was not very picky about where to record. This whole process has taught me to find the beauty where I am.

Does music hold a specific relationship to location for you? Are there compositions that sound like certain places? If so, can you give me an example?

Music and landscape are very important to me. It hasn’t been until the past three years or so that I began to combine both activities together. I’m a geospatial tech, so I am constantly surrounded by maps, topography and the understanding of landscape, and there is so much art within geography. That perspective has pushed me to think about points on a map as moments, small markers of countless changes and quiet significance. I wouldn’t say I am trying to make the compositions sound like a place; more so I am attempting to capture a moment of time in a location — an audible snapshot of what took place and where. It was a moment shared with the ecosystem that exists with or without me.

Are these recordings all single takes made at individual recording locations, or are we hearing snippets of natural sound layered from multiple separate sessions and places? The name of each work is a date; is that the date each piece was recorded?

All of the recordings are single takes made at different locations; all of the sounds are from the session, and no additional field recordings were added. For both Microfolk and Winter Music, many songs were created on same-day sessions. When I would go out with Courtney Werner during the Microfolk sessions, we could complete 3 to 5 pieces, depending on the day or where we were at creatively. For Winter Music, the names were mostly the dates the pieces were recorded. I would limit it to at most two pieces per session (which is why you will see the same date on a couple of songs). Winter Music was complicated because my hands lost feeling fairly quickly. With setting up then going straight into improvising, I could only record for roughly 15 to 20 minutes before I would mentally and physically break. This limited how much material I was actually able to record.

Can you offer some insight into your improvisation process? Do you go out into the field with a preconceived score in the back of your mind? Or is everything improvised on-site? Do you find the idea through experimentation in the field?

Everything is improvised on the spot — from where we end up from the trail, to the loops that texture every song, to what was played over it. The tape loops are an interesting improviser. I try not to overthink how each loop will play with the others. I will often record three different loops without ever listening back. So when all three cassettes start playing back, it automatically transports you into its own world. It is good practice to improvise over any sound — like, how do you make the pieces fit? I spend half of my existence overthinking things, so by creating this way, it just allows me to practice acceptance and how to creatively blend into an audible landscape.

As far as tools go, can you share what technology you used to make these recordings? Were you out there with a laptop mixer and some microphones? A handheld digital recorder, or something else?

The tools were pretty simple. For both Microfolk and Winter Music, the setups were the same. Each session utilized a Zoom H6, two mic stands, two condenser mics, three cassette players, cables, a single pair of headphones and our instruments. Headphones were only used to check levels but were not used during the recordings. The three tape players were positioned right, left and center of the Zoom microphones. The two condenser mics were then placed in front of each instrument. All I had to work with were three final stems.

For Microfolk that would be the tape loops, my dulcimer tracks and Courtney Werner’s violin or Chaz Prymek’s guitar.

With Winter Music, I really only had two stems to work with: the tape loops and harmonium, or loops and guitar/voice. This is where things get tricky, because you are so limited. I am not doing overdubs, so I have to make it work during editing and mixing. I would run into being disappointed with how much bleed-through occurred. But the limitations create a raw, honest quality in the music, and that’s what gives it meaning for me.

Were there major creative differences for you between the outdoor recording process of Winter Music and your Microfolk trilogy?

The main creative difference was seeing how the elements’ change affects creative decisions or flow state. With Microfolk, we mostly dealt with the extreme heat, humidity and sweat. It was very hot for some sessions but mostly tolerable. Winter Music was the other extreme, and I found it fascinating how quickly my hands became useless. Your mind knows how you want to play the next part, but my fingers couldn’t physically move how I wanted them to.

I was surprised by how quickly I was able to get into the “flow state” once the tape loops started going, but there were also several times when I was just recording and hoping I could find something usable. The thing about being confined to an outdoor session is there may be some days when you are not feeling particularly creative, and so your mind is not as in it. I found it interesting that even these sessions still had an emotion I was not expecting.

Working in the depths of winter, did you have many technical challenges? I imagine your guitar neck must have taken a beating, and your batteries must have as well.

The technical challenges weren’t horrible. I may or may not have messed up my mics — they seem fine on certain days. My guitar neck shrank, so my frets would be sticking over the neck, which would give me these tiny cuts anytime I moved. The tape players seemed to be okay. They made things indestructible back in the day.

Your piece “wm feb17 25” includes some very mechanical sounds in combination with a woodwind instrument. Can you share what elements make up that work?

I was using a bansuri flute for this entire piece. The mechanical sounds are very closely recorded loops of me making weird sounds on the flute and voice. I believe this piece had four tape loops, mostly of different “breath” takes. Then my improvisation part was me switching between breath as noise and small melodic breakthroughs.

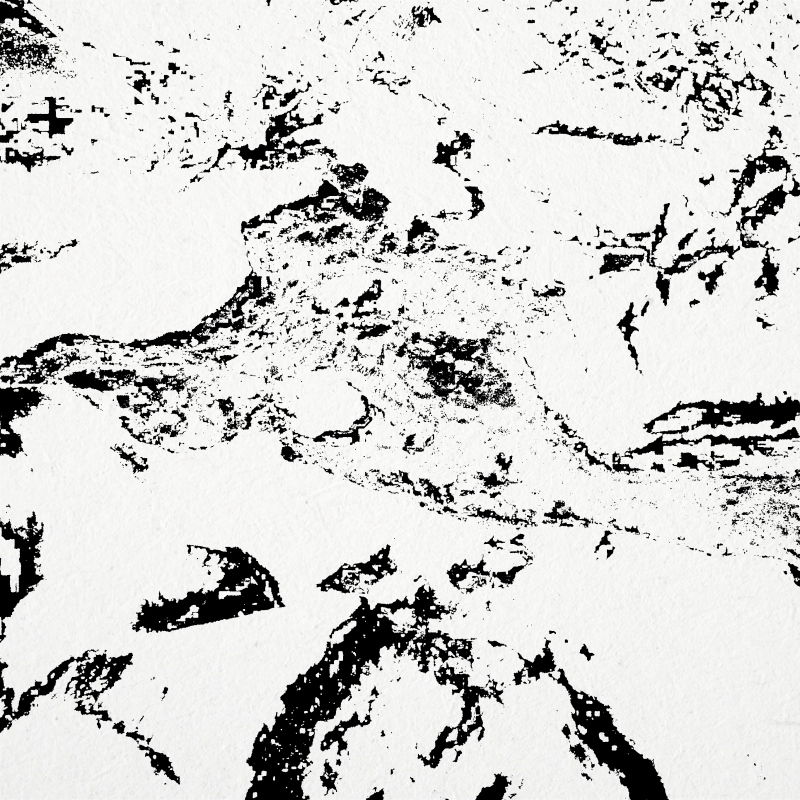

Can you offer some insight into the cover of this album? Who is the artist behind it? Why did you choose it?

The album cover was a picture of the creek from Track 4. My partner, Kim Awa, who has done the majority of my album covers, altered the creek image to stay pretty minimal, but the idea was to strip the color and depersonalize the scene to its most basic shapes and contrast. This is meant to slightly confuse our eyes when trying to decipher what the image is, similar to how winter can make us feel constricted as the color strips away.

Were there any other creators who influenced you toward making this work? If so, how did their own work direct you toward Winter Music? This could be any type of creative undertaking, not just another musician.

To be honest, there wasn’t a single creator who directly pushed me toward making Winter Music. Most of what I listen to is singer-songwriter music, usually the same 10 songs on repeat, and they don’t necessarily influence what I end up making. What shapes me more are the people close to me who create from a place of sincerity: Chaz Prymek (Lake Mary), Courtney Werner, Saapato and my partner, Kim Awa. Their work feels grounded, lived-in and honest, and it reminds me that creating isn’t about perfection but about presence. I want to thank both Aural Canyon and Scissor Tail Records for their support with these releases. It has meant the world.

We’re also in a strange cultural moment when everything feels overly polished and homogeneous, and that atmosphere pushes me to go in the opposite direction. I think I’m most influenced by the desire to make something human and imperfect, to contribute a piece of sound that feels real. It is something that makes me feel, and hopefully allows someone else to feel, too.

Is there a specific piece on Winter Music that you are especially proud of? If so, what work is it and why?

My favorite pieces are the first track (“wm jan14 24”) and the fourth track (“wm jan23 24”). The first track was also the first piece recorded for the Winter Music sessions. I think it is stark, cold, raw but beautiful. Track 4 was written along a half-frozen creek covered in snow. The water is almost harsh, but the guitar and melody counteract the harshness with a meditative beauty. This was one of the coldest sessions, but the music almost seems to provide its own warmth.

Did working in these cold landscapes change the way you thought of improvisation? After this project and Microfolk, have you found that working in these outdoor conditions enables you to reach a new creative pathway or let your music head in a direction that it would not otherwise be able to in the traditional studio environment?

Working in the cold didn’t necessarily change the way I think about improvisation — I honestly don’t think much about how to approach improvisation in general. But doing this record, along with Microfolk, has definitely opened a new creative pathway for me. It feels like I finally found the voice I had been searching for. Creating music this way is something I’ll always keep doing. I’ll work on other projects too, but sessions like these act as a musical and mental reset that I really need. They’re also the most meaningful pieces of music I make. I remember the exact moment and the landscape around me, and the recordings always take me back there — something I’d never experience in a traditional studio.

I make music for myself, and working this way makes me feel genuinely happy and proud.